Using basic tools found at a local hardware store, the duo came up with a painkilling device small enough to hold on one’s lap. They called their machine TENS, which is short for transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. The machine used pads filled with electrodes to send electrical currents through the skin (transcutaneous meaning “applied across the depth of the skin”) and to the tissue and nerve strands beneath it. This created a tingling sensation—a twitching, if the signals were high enough—and in turn, translated the pain signals within the nerves into something that’s pleasant rather than unpleasant, sometimes even creating endorphins, which is the body’s natural painkiller.

After building the first TENS machine, the duo sought to try it out, and chose a patient who had lost a leg and was suffering from phantom limb pain. This patient’s issue was a perfect trial-run for the machine, as phantom pain comes from nerves sending confused signals to the brain for the limb that is no longer there. If the nerve signals could be modified, then the phantom pain would theoretically go away.

The trial run was a success. After Hagfors and McDonald took the machine to the patient at a local hospital, the test-subject was immensely satisfied and expressed interested in gaining access to TENS as a regular treatment to his pain.

With these positive results on their radar, Hagfors and McDonald knew that it was going to be more than worthwhile to invest in perfecting their machine and to find a way to make them regularly available to pain patients. In 1971, Clayton Jensen became the third man to join their team, and the trio formed their company, Stimulation Technology, or Stimtech.

Stimtech’s primary goal was to make the public aware of TENS as an alternative solution to pain of all sorts, whether it be phantom limb pain, back aches, sports related injuries, etc. In the 1970s, painkiller addiction and dependency—by today’s standards, an epidemic—were already becoming prominent. Stimtech hoped to make TENS a healthier available option.

Gradually they spread the word. Doctors held educational sessions with patients who could then take home their own TENS and give the treatment to themselves. It looked like the device would take off as something that could give patients the control they sought over their pain. Other companies in the states and around the world tried their hands at similar TENS machines, but Stimtech’s remained on top.

Johnson and Johnson Suppressed Electrotherapy Technology

Success to the three inventors behind Stimtech would have meant reaching as many pain patients as possible with this alternative treatment. But the high-cost production that Stimtech had been using meant that each TENS machine had to sell for $300-$500, a high price to pay for many, especially in the 1970s. Stimtech’s next step was to find a way to fund both the research necessary to create a smaller, more affordable machine that could provide the same results, as well as the marketing they would have to do to really push the TENS machine onto the minds of doctors and patients who were so used to treating pain with medication.

By 1973, Johnson and Johnson, the makers of Tylenol and many other pharmaceuticals and medical devices, already owned a large portion (over 30%) of Stimtech’s stocks. In 1974, the two companies came to an agreement that resulted in Johnson and Johnson purchasing the rest of the stocks, making Stimtech a subsidiary owned by Johnson and Johnson. Within this deal was the agreement that Johnson and Johnson would market the TENS machine internationally and provide the resources needed for additional research and development, putting everything they had behind the Stimtech product, including their own label which would aid in credibility. The company was bought for $1.3 million, and the trio of inventors were promised up to $7 million in additional profits.

After five years, these promises were not fulfilled. There was no international marketing, no Johnson and Johnson label behind the TENS machine and, perhaps worst of all, Johnson and Johnson refused to let the original owners buy back Stimtech and a noncompete clause in the contract prevented them from starting up a new company.

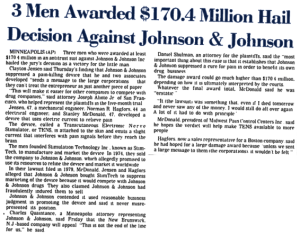

In 1979, Hagfors, McDonald and Jensen sued Johnson and Johnson for fraud and breach of contract. Their theory was that the large company bought Stimtech not to help expand awareness and use of TENS, but to suppress it and its development. As Tylenol was by then a well-known painkiller and a primary product owned by Johnson and Johnson, it was suspected that the company was threatened by the development of an alternative to pain treatment. While they insisted that they weren’t suppressing its development and just had trouble finding its marketability, it’s still surmised that their alleged support of Stimtech was actually an attempt to end the use of the TENS machine. So Johnson and Johnson suppressed electrotherapy technology. In terms of the case for fraud, the courts found Johnson and Johnson guilty and the parent company was forced to pay $170.4 million dollars to Stimtech.

Since the court case, other manufacturers have come up with new and improved ways of making TENS therapy available to people everywhere. If Johnson and Johnson was hoping to suppress the advancement of this technology, they could only hold it back for so long. A drug-free, addiction-free solution to pain that works short and long term makes sense as the next big wave in medical development.

.png?width=320&height=80&name=11.3.17-Logo-with-passion-colors-and-roboto-font-AI-v3-(320-x-80).png)

%20jpg-1.jpg?width=300&name=11.13.17%207070%20Banner%20(300%20x%20250)%20jpg-1.jpg)